From farms to factories, from smartphones to kitchen taps, global water consumption and demand are rising, driven by agriculture and industry. At the same time, reserves are shrinking, worsened by the climate crisis, overuse, and unequal access. Efficient, fair, and sustainable management is becoming a critical global priority.

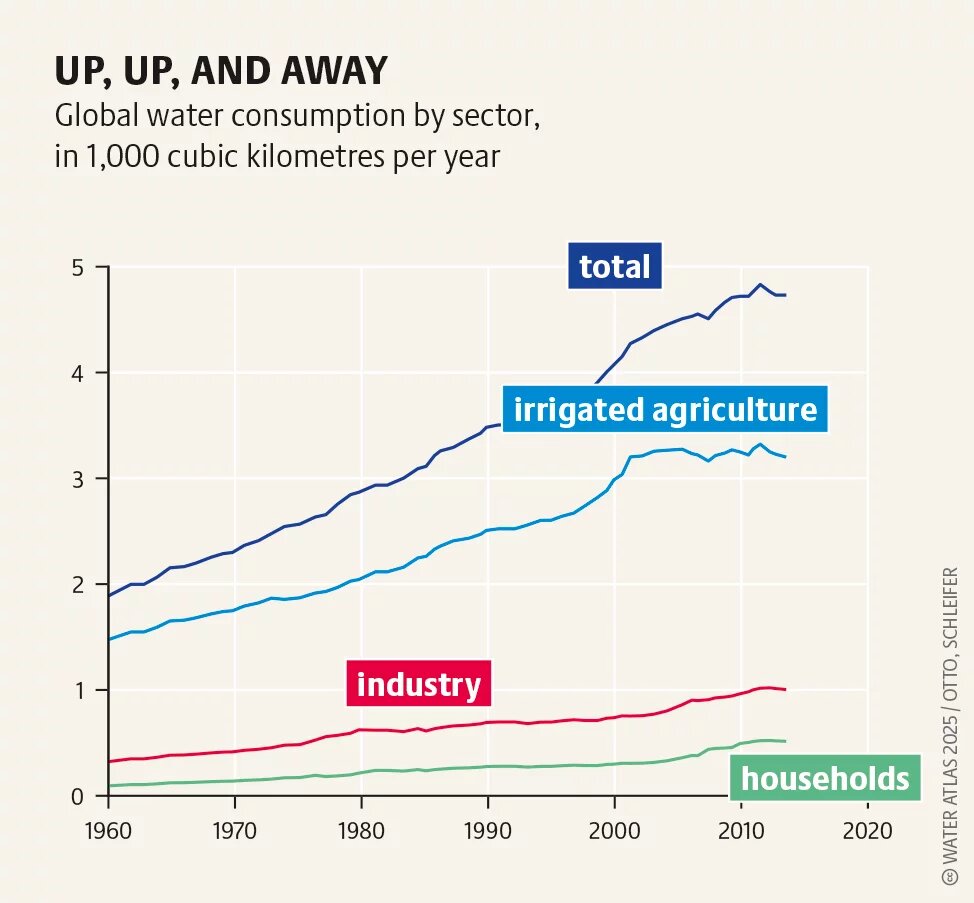

Freshwater is one of the most vital – yet increasingly strained – natural resources on Earth. Today, the total amount of freshwater withdrawn from rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and aquifers exceeds 4,000 cubic kilometres per year. Over the past century global water use has increased sixfold, according to the United Nations, due to a combination of population growth, agricultural expansion, industrialisation, and urbanisation. While water withdrawal has plateaued in high-income countries, largely due to efficiency gains, demand continues to rise in emerging economies. That means global water demand is still projected to grow by an additional 20 to 30 percent by 2050, driven largely by cities, energy production, and manufacturing. The climate crisis, pollution, and over-extraction are reducing the supplies available in many regions. Groundwater reserves often serve as the hidden backbone of water security, and they are being depleted faster than they can replenish, especially in India, China, Pakistan, and the western United States. Unless managed carefully, these trends could push more countries into water stress. The future of freshwater will depend not only on how much we use, but also how we allocate and manage it across competing sectors.

Accounting for nearly 70 percent of all freshwater withdrawals, agriculture dominates the global picture of freshwater use. However, industries also play a major role and can exert intense local pressure. Industry makes up roughly 19 percent of global water withdrawals, and households around 11 percent, though these shares vary significantly by country.

In high-income countries, such as Germany or Canada, industrial use can constitute the majority of national freshwater withdrawals. Depending on the country, water-intensive industries can include thermal power generation (which uses water mainly for cooling), mining, chemicals, metals, and textiles. Making steel, refining oil, and processing pulp and paper all require substantial volumes of water. The electronics and semiconductor industry also uses ultrapure water in its manufacturing processes.

Although industrial water is often reused or recycled more than water used in agriculture, the discharge of heated or polluted water can have serious environmental consequences. While industries may consume less water than farms, they may have a greater impact per unit of water withdrawn, especially where freshwater ecosystems are already under stress. Whereas we often associate water use with drinking, cooking, or farming, vast amounts of water are also embedded in the manufacture of products that we use every day. This so-called hidden or virtual water is embedded in the items we wear, use, and dispose of, often without realizing their environmental impact. Paper, plastics, and electronics all have substantial water footprints. For example, manufacturing a single smartphone may require as much as 12,000 litres of water, used in mining rare metals, assembling components, and cooling during production. Similarly, a laptop can require tens of thousands of litres to make, primarily to make microchips, which requires large amounts of ultrapure water. The textile and fashion industry is another major water user. Producing synthetic fabrics like polyester involves water-intensive chemical processes, while dyeing and finishing garments can cause pollution if the waste water is untreated. A pair of leather shoes uses thousands of litres, mostly in tanning and processing the leather. Even producing a sheet of office paper requires around 10 litres of water. All of these water costs often occur far from where products are sold, making conscious consumption and sustainable manufacturing practices essential in a water-scarce world.

As the climate crisis alters rainfall patterns and makes droughts more frequent, conflicts over water allocation are increasing. When water becomes scarce, who gets priority: farms, factories, or families? In most countries, households and essential services (such as hospitals and schools) are generally prioritised. Yet the reality plays out in more complex ways. In India, some regions have diverted water from agriculture to urban centres to meet drinking water demand during droughts. In contrast, parts of California have prioritised high-value crops such as almonds even during periods of severe water shortage, sparking debates over public versus private water rights.

In 2018, drought and mismanagement meant that Cape Town in South Africa only narrowly missed Day Zero, when the city's water reserves would be fully drained. Emergency rationing was imposed, where households were allowed only 50 litres per person per day. Water use by industries and golf courses drew public scrutiny. Similar tensions have emerged in Chile’s mining regions, Spain’s agricultural valleys, and Jordan’s urban–rural divide.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer. The challenge lies in balancing social, economic, and ecological needs, especially as the climate crisis makes the future of water harder to predict. Transparent governance, robust legal frameworks, and inclusive water planning will be critical to making those choices fair and sustainable.